Kulish, Mykola

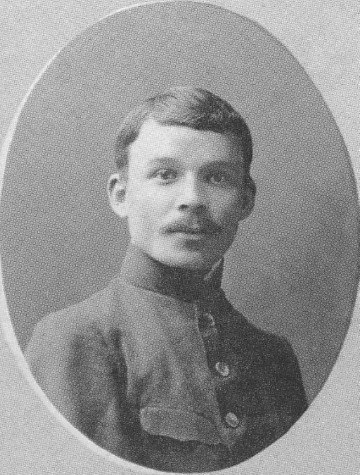

Kulish, Mykola [Куліш, Микола; Kuliš], b 18 December 1892 in Chaplynka, Tavriia gubernia, d 3 November 1937 in Sandarmokh, Karelia region, RSFSR. The most famous Ukrainian playwright of the twentieth century. After his mother’s early death, Kulish spent most of his childhood in orphanages and charity homes. He finished his early education thanks to the financial support of distant acquaintances. He began writing satirical poems and plays as a gymnasium student in Oleshky. After graduating from the gymnasium in Poti (now in Georgia) in 1914, he studied history and philology at Odesa University. Kulish’s university education was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. He was conscripted into the Russian Army, took part in military campaigns as an infantry officer in Galicia, Volhynia, and Belarus, and thus came into contact with the Ukrainian national movement. In 1917 Kulish was wounded at the front and discharged. Later that year he served as head of the town council in Oleshky. He participated in the Ukrainian Struggle for Independence (1917–20), organizing a guerrilla regiment to fight the Russian Volunteer Army in Southern Ukraine and distinguishing himself as its commanding officer.

Under early Soviet rule, Kulish began working for in the Commissariat of People’s Education (NKO) in Odesa in 1922 and served as a school inspector in the Odesa region. After the dissolution of Odesa gubernia in 1925, he was transferred to Zinovivske (now Kropyvnytskyi) to work as an editor of a local newspaper, and in the fall of that year, on the recommendation of People’s Commissar Oleksander Shumsky, he moved to Kharkiv, where he was appointed director of the NKO’s All-Ukrainian Drama Committee.

Kulish had joined the proletarian writers' group Hart in 1924, and after moving to Kharkiv he met many of the group’s other members. One of them, the famous writer and polemicist Mykola Khvylovy, had a great impact on Kulish’s writing and views. Kulish was also profoundly influenced by Ukraine’s leading theater director, Les Kurbas, who staged several of Kulish’s plays at his Berezil theater. In 1925 Kulish was elected to the presidium of the new writers' group Vaplite, and from November 1926 he served as its president. In 1926 Kulish also founded and headed the Ukrainian Society of Dramatists and Composers in 1926, and in 1927 and 1929 he took part in the famous Literary Discussion and Theater Dispute in Soviet Ukraine. After Vaplite’s forced dissolution in January 1928, he was a founding contributor to the literary and art journal Literaturnyi iarmarok. In 1927 and 1928 he was also a member of the editorial board of the prominent Soviet Ukrainian journal Chervonyi shliakh. In late 1929 Kulish became a member of the presidium of a new writers' organization, Prolitfront.

When the Soviet regime forced Prolitfront to disband in January 1931, it no longer viewed Kulish as a persona grata and did not allow him to join the only officially sanctioned writers' organization, the All-Ukrainian Association of Proletarian Writers. In June 1934 his plays were condemned as nationalist and harmful, and he was labelled a ‘counterrevolutionary’ and expelled from the Communist party. In December 1934 the NKVD arrested Kulish. Soon after he was tried as a member of a fictitious ‘all-Ukrainian terrorist center of Borotbists’ and sentenced to ten years in an isolation cell in an NKVD prison on the Solovets Islands in the Soviet Arctic. He was subsequently murdered at the landmark of Sandarmokh in Karelia during the mass executions of political and other prisoners marking the twentieth anniversary of the October Revolution of 1917.

Kulish wrote fourteen plays. Six of them were published during his lifetime. He became famous after the stage success in 1924 of his first play, 97, which is generally considered the beginning of Soviet Ukrainian drama and the first major play written in the USSR as a whole. It was, however, not staged as Kulish had written it, but was censored by first production’s director, Hnat Yura, who changed Kulish’s tragic finale to an ideologically correct, optimistic one. Kulish’s subsequent plays shared similar fates and were heavily censored or banned outright by the Soviet authorities. As a dramatist, Kulish initially devoted his efforts to portraying the postrevolutionary struggle among the peasantry of Southern Ukraine. Besides 97, the plays on that subject included Komuna v stepakh (A Commune in the Steppes, 1925) and, several years later, the final work in his ‘village trilogy’—Proshchai, selo (Farewell, Village, 1933). The Soviet censors forced him not only to revise the latter, but even to rename it Povorot Marka (Marko's Return, 1934), deeming the original title an allusion to the destruction of the traditional Ukrainian village by Soviet collectivization and the Famine-Genocide of 1932–3.

During the second phase of his dramaturgy, Kulish turned to writing comedy and satire. In Otak zahynuv Huska (That’s How Huska Perished, 1925) and Khulii Khuryna (1926), which harked back to Nikolai Gogol’s themes and motifs, he ridiculed the attitudes and prejudices of both prerevolutionary Russian imperial society and of the new Soviet bureaucracy. The culmination of his of demythologization of the Bolshevik revolution was his melodrama Zona (Ergot, 1926), which Kulish later reworked and renamed Zakut (Dead End, 1929). He also wrote a ‘linguistic comedy,’ Myna Mazailo (1929), where, in a manner akin to Molière, he satirized the political and social impact of the Soviet policy of Ukrainization.

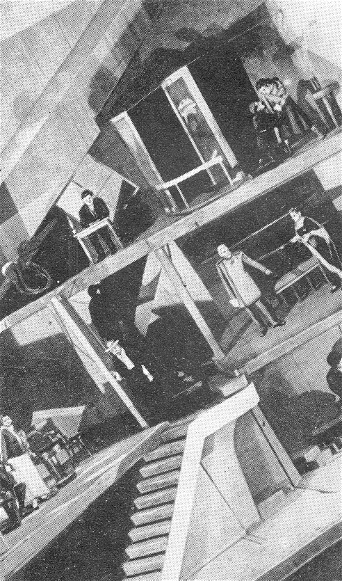

During his most productive and creative period as a playwright and close collaborator of Les Kurbas and the Berezil theater, Kulish abandoned the style and tools of traditional, realist dramaturgy. Instead, he experimented with expressionist and avant-garde writing, often combining it with elements of the Ukrainian puppet theater (vertep) and school dramas popular of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. His most important trilogy of that period—Narodnii Malakhii (The People's Malakhii, 1927), Patetychna sonata (Sonata pathétique, 1930), and Vichnyi bunt (Eternal Rebellion, 1932)—addresses the stark contradictions between Ukrainian national aspirations and Soviet reality and deals with the inherent conflict between an individual’s aspirations and a society’s principles. Besides depicting the disintegration of revolutionary idealism, the trilogy addresses the universal dilemmas of human existence in a manner similar to that of French existentialist drama of the late 1930s. Kulish’s portrayal of these universal themes is most darkly and pessimistically expressed in his drama Maklena Grasa (1933).

Apart from many productions of 97 and Komuna v stepakh, few of Kulish’s plays were staged during his lifetime. Khulii Khuryna, Zona, and Patetychna sonata were banned outright in Soviet Ukraine. The latter play was, however, translated into Russian and simultaneously produced at the Kamernyi Theater in Moscow by Aleksandr Tairov and the Bolshoi Drama Theater in Leningrad by K. Tverskoi from December 1931 to March 1932. A bowdlerized German translation, which attracted the admiration of Bertold Brecht, was published in Berlin in 1932. Perhaps the most important productions of Kulish’s plays were those Kurbas directed at the Berezil theater. However, the authorities only allowed Myna Mazailo to be performed for a longer time. Narodnii Malakhii was banned after several performances, and Maklena Grasa was banned a few weeks after its dress rehearsal, which was monitored by armed GPU officers.

At the time of his arrest, all of Kulish’s manuscripts were confiscated, and most of them were subsequently destroyed. Some of his plays were miraculously saved and smuggled into Western countries by Ukrainian refugees during the Second Wold War. Others were preserved only in Russian translation. Some, including Taki (Such Ones, 1934) and Kulish’s screenplay Paryzhkom (The Paris Commune, 1934) were irretrievably lost.

The first edition of Kulish’s selected plays and memoirs about him was edited by Hryhory Kostiuk and published in New York in 1955. After Kulish’s posthumous ‘rehabilitatation’ in 1956, three editions of his selected plays appeared in Ukrainian in Kyiv (1960, 1968, 1969), and one in Russian in Moscow (1964, 1980). The fullest edition of his collected works (in two volumes) was edited by Les Taniuk and published in Kyiv in 1990. Natalia Kuziakina wrote three monographs on Mykola Kulish published in 1962, 1970, and 2010.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kuziakina, Natalia B. Dramaturh Mykola Kulish: Literaturno-krytychnyi narys (Kyiv: Radians'kyi pys'mennyk, 1962)

Kysel'ov, Iosyp. ‘Mykola Kulish,’ in his Dramaturhy Ukraïny: Literaturni portrety, 206–92 (Kyiv: Dnipro, 1967)

Kuziakina, Natalia B. P’iesy Mykoly Kulisha: Literaturna i stsenichna istoriia (Kyiv: Radians'kyi pys'mennyk, 1970)

Revutsky, Valerian. ‘Mykola Kulish in the Modern Ukrainian Theatre,’ SEER, July 1971, 355–64

Pikulyk, Roma Bahrij. ‘The Expressionist Experiment,’ CSP 14 (1972), no. 2: 324–44

Kulish, Mykola. Sonata pathétique, trans George S. N. Luckyj and Moira Luckyj, intro by Ralph Lindheim (Littleton, Colo.: Ukrainian Academic Press, 1975)

Smyrniw, Walter. ‘The Symbolic Design of Narodnyy Malakhiy,’ SEER, April 1983, 184–96

Sherstiuk, Tetiana H., comp. Ukraïns'kyi pys'mennyk M. Kulish (1892–1937): Bibliohrafichnyi pokazhchyk (Kharkiv: Kharkivs'ka derzhavna naukova biblioteka im. V. H. Korolenka, 1993)

Kulish, Mykola. Zona / Blight: A Play in Three Acts, trans. Maria Popovich Semeniuk and John Woodsworth (New York, Ottawa, and Toronto: Legas, 1996)

Semenchuk, Ivan R. ‘Slukhaiu muzyku liuds'koï dushi’: Stanovlennia Mykoly Kulisha, dramaturha. Literaturnyi profil' (Kyiv: Biblioteka ukraïntsia, 1997)

Prats'ovytyi, Volodymyr S. Ukraïns'kyi natsional'nyi kharakter u dramaturhiï Mykoly Kulisha (Lviv: Svit, 1998)

Stech, Marko Robert. ‘The Concept of Personal Revolution in Mykola Kulish’s Early Plays,’ JUS 27, nos. 1–2 (2002): 107–24

Kuziakina, Nataliia. Traiektoriï dol' (Kyiv 2010)

Valerian Revutsky, Roman Senkus, Marko Robert Stech

[This article was updated in 2006.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)