Bukovyna

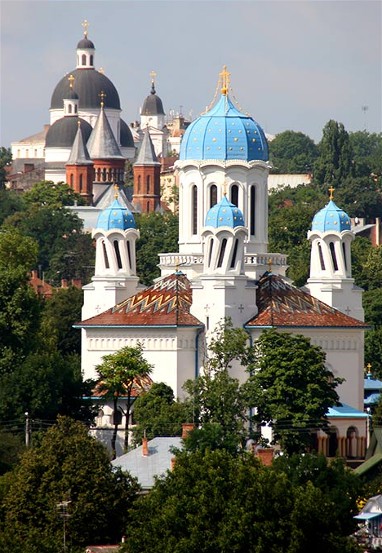

Bukovyna (Bukovina, Bukowina, Bucovina) [Буковина]. (See map: Bukovyna.) The territory between the middle Dnister River and the main range of the Carpathian Mountains, around the source of the Prut River and the upper Seret (Siret) River, the border area between Ukraine and Romania. Today Bukovyna is divided between Ukraine (incorporating Chernivtsi oblast or most of northern Bukovyna) and Romania (containing most of the Suceava region or southern Bukovyna). The name of this territory is derived from its great beech (buk) forests and dates back to the 14th century when it designated the lands on the Moldavian-Polish border.

Bukovyna is a transitional land between Ukraine and Romania. From a historical perspective it is a strategically important border area between Galicia and Moldavia, as it lies at the northwest entrance to Moldavia. Bukovyna's transitional location influenced its history; it belonged to the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia, then to Moldavia. Polish and Hungarian influences intersected here in the 14th and 15th centuries. In 1919–40 and 1941–4 all of Bukovyna belonged to Romania. It was only in 1940 that Bukovyna was divided, along ethnic lines, between Ukraine and Romania. Bukovyna's territory consists of 10,440 sq km, of which about 5,500 belong to Ukraine. The population in 1930 was 853,000, about 520,000 of which became citizens of the Ukrainian SSR in 1940.

Geography and economy. The southwestern half of Bukovyna consists of the Carpathian Mountains, which are divided into two ranges: the crystalline Maramureş-Bukovynian Upland and the flysch Hutsul Beskyd mountains. Adjacent to the Carpathians lie the Bukovynian Carpathian foothills. Then comes a part of the Pokutian-Bessarabian Upland located between the Prut River and the Dnister River. The climate of Bukovyna is temperate continental, modified by the elevation. For example, the temperature at Vatra Dornei (at 789 m) is -6.4°C in January and 14.2°C in July, and the annual precipitation is 745 mm; at Chernivtsi (at 252 m) the temperature is -5.1°C in January and 20.1°C in July and the annual precipitation is 619 mm. About 40 percent of the area is forest, up to 20 percent is pasture, and over 30 percent is cultivated land. The 270,000 ha under cultivation produce corn, rye, wheat, oats, potatoes, seed grasses, and sugar beets. In 1930 about 75 percent of the population was employed in agriculture. The crystalline band contains such useful minerals as iron ore, manganese ore, lead, silver, and copper ores. The Carpathian foothills contain salt and cement marls. The main industry is woodcrafts, which produces significant exports, followed by the food industry (sugar refining, milling, brewing), tanning and shoemaking, rubbermaking, and knitting. In general industrial development is low, although industrial growth was somewhat greater under Romanian rule than it was before 1918, when Bukovyna had to compete with Austrian and Czech industries. The railway network (5.1 km per 100 sq km or 6.3 km per 1,000 inhabitants) and highway network are well developed.

Population. At the time Bukovyna came under Austrian rule it was sparsely settled. In 1775 it had 75,000 inhabitants or 7 people per sq km. Eventually, through natural growth and immigration, its population increased to 208,000 in 1807; 371,000 in 1827; 447,000 in 1857; and 642,000 in 1890. At the end of the 19th century the population outflow (emigration to the Americas) exceeded the influx, and so the rate of population growth declined: in 1900 the population was 730,000; in 1930 it was 853,000; and in 1941 it was 792,000. In 1930 there were 82 inhabitants per square kilometer, and 27 percent of the population lived in towns. The largest towns were Chernivtsi (the center of the region) with 112,000 inhabitants, Suceava with 17,000, Rădăuţi with 17,000, Seret with 10,000, Cîmpulung Moldovenesc with 10,000, Sadhora with 9,000, and Storozhynets with 9,000. Ukrainians and Romanians constitute the majority of the population. According to the Austrian census of 1910, Ukrainians numbered 340,000 or 40 percent of the population (29.2 percent according to the inaccurate Romanian census of 1930), while Romanians numbered 290,000 or 34 percent of the population (379,000 or 44.5 percent of the population according to the Romanian census).

Other ethnic groups appeared only during the Austrian period: in 1910 Jews numbered 95,000, constituting 11 percent of the population (92,000 or 10.8 percent according to the 1930 census); Germans numbered 75,000 or 9 percent (75,500 or 8.9 percent); Poles numbered 25,000 or 3 percent (30,600 or 3.6 percent); and smaller groups, such as the Hungarians, Russian Old Believers, Slovaks, and Armenians, totaled 25,000 or 3 percent of the population. The Jews, Germans, and Poles lived primarily in towns (most of them in Chernivtsi). Although the Germans constituted only one-tenth of the population, the German language, which was used by Jews as well as Germans, was widely spoken in Bukovyna, especially during the Austrian period. Nowhere else in Ukraine were German cultural influences and, in the Austrian period, German political influences as strong as in Bukovyna. The ethnographic border that divides Bukovyna into Ukrainian and Romanian sections runs from Kyrlybaba in the south, through Ruska Moldavytsia, Banyliv-Pidhirnyi, Storozhynets, and Chernivtsi, to Ridkivtsi on the Bessarabian border in the north. From the Ukrainian ethnic area a long Ukrainian ethnic peninsula, containing the town of Seret, extends along the Moldavian border from Chernivtsi to Suceava in the south. On the other side Romanian settlements extend up to Chernivtsi. In 1930 Ukrainians constituted 65 percent, Jews 12 percent, Romanians 11.5 percent, Germans 5 percent, and others 6 percent of the population in the Ukrainian ethnic area (5,300 sq km and 460,000 inhabitants). At the same time, in the Romanian ethnic area (5,140 sq km, 390,000 inhabitants), Romanians constituted 64 percent, Germans 11 percent, Jews 10 percent, Ukrainians 9.5 percent, and others 5.5 percent of the population.

The present political border between Ukraine and Romania does not coincide with the ethnic border: Romania contains the southern part of the Ukrainian ethnic peninsula with Seret and a string of mountain villages, while Ukraine contains the Romanian ethnic wedge that extends to Chernivtsi. Romanian Bukovyna has about 30,000 Ukrainians or 9 percent of the region's total population, while Ukrainian Bukovyna has almost 95,000 Romanians or 18 percent of the region's population. The present ethnic composition of the population has changed somewhat as a result of the German exodus and the extermination of most of the Jews during the Second World War.

History

To 1774. In early times Bukovyna was inhabited by the Thracian tribes of the Getae and Dacians. From the 3rd to the 9th century AD various nomads traversed Bukovyna: in the 4th century East Slavic tribes began to appear and the region was part of the Antean state (see Antes); in the 9th century the Tivertsians and White Croatians were the local inhabitants.

In the 10th century Bukovyna became part of the Kyivan Rus’ state. When this state was divided at the end of the 11th century, Bukovyna was eventually incorporated into the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. The church in Bukovyna was administered by Kyiv metropoly until 1302, when it was transferred to Halych metropoly. With the Tatar invasion in 1241 Bukovyna fell under Tatar domination. At the beginning of the 14th century in northern Bukovyna an autonomous territory called the Shypyntsi land arose. When the Hungarian king Louis I defeated the Tatars in 1342, southern Bukovyna came under Hungarian rule. During this period Romanians from Transylvania and the Maramureş region began to settle in Bukovyna. Voevode Bogdan I, the founder of the Moldavian state, freed Bukovyna from Hungary (1359–65). From then to 1774 Bukovyna belonged to Moldavia and shared its fate. From 1387 to 1497 Moldavia recognized the nominal supremacy of Poland. In this period the people of Bukovyna took part in the Mukha rebellion against the Polish and Moldavian nobles (1490–2). From 1514 Moldavia recognized the supremacy of Turkey, and towards the end of the century it became increasingly dominated by that country. The Romanianization of Moldavia, where the Ukrainians played an important role and literary Ukrainian was the official language, and of Bukovyna became more intense after 1564, when the capital of Moldavia was moved from Suceava in Bukovyna to Iaşi. Yet Bukovyna maintained its ties with the rest of Ukraine. Cossack regiments (under Ivan Pidkova, Severyn Nalyvaiko, and Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny) fought on Moldavian territory against the Turks. Some of Bukovyna's population participated in Bohdan Khmelnytsky's national rebellion. Tymish Khmelnytsky died near Suceava in 1653 fighting a coalition of Poland, Transylvania, and Wallachia.

In the cultural sphere, Bukovyna benefitted from the achievements of the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood and the Kyivan Mohyla Academy. From 1401 to 1630 an independent metropoly (to which the eparchy of Rădăuţi was subordinated) existed in Suceava. From 1630 to 1782 Suceava metropoly came under the metropolitan of Iaşi. From the 16th to the mid-19th century the opryshoks were active in the mountainous part of Bukovyna bordering on Galicia; among them was the famous Oleksa Dovbush. At the end of the Moldavian period Bukovyna was sparsely populated and was economically and culturally backward.

1774–1918. Taking advantage of the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–74, Austria annexed the part of northern Moldavia that included Chernivtsi, Seret, Rădăuţi, and Suceava. Turkey and Moldavia had no choice but to accept this action. The new administrative entity was given the name of Bukovyna (first used in a document in 1412). The Austrian government brought in a series of reforms: in 1781 serfdom was abolished; in 1782 a separate Bukovynian eparchy was established and in 1783 subordinated to the Serbian metropolitan in Sremski Karlovci; in 1873 the eparchy was elevated to an independent metropoly with Yevhen Hakman as the first metropolitan; schools were then founded. Austria opened new sources of immigration into Bukovyna from the neighboring lands—Transylvania, Moldavia, Galicia—as well as from the heartland of Austria and Germany. As a result, there was an influx of Germans, Poles, Jews, Hungarians, Romanians, and Ukrainians, and by the beginning of the 19th century the population of Bukovyna was three times that of 1775. German was the official language in Bukovyna, although Romanian and Ukrainian could be used in transactions with the government.

At first Austria held Bukovyna under military rule. From 1774 to 1786 it was governed by the generals G. Splényi and K. von Enzenberg. In 1787 it was attached as a separate region to Galicia, a status it retained until 1849. During this period, in 1842–5 and particularly in 1848–9, peasant revolts broke out in the Hutsul area of Bukovyna. The peasants demanded social and political rights. Corvée was abolished in 1848. Then elections to the parliament in Vienna were held, and five Ukrainians (among them Lukian Kobylytsia), two Romanians, and one German were elected to represent Bukovyna. On 4 March 1849 Bukovyna became a crown land with an autonomous administration and its own president. It attained full autonomy in 1861, when it was granted a special statute, a provincial diet (its first marshal was Bishop Yevhen Hakman), and its own executive.

Writers such as Yurii Fedkovych, Sydir Vorobkevych, and later Olha Kobylianska were the heralds of the 19th-century Ukrainian renaissance in Bukovyna. The first Ukrainian association, known as Ruska Besida in Bukovyna, was established in 1869. In 1870 the Ruska Rada society was founded, and in 1875 a student organization called Soiuz, in which Russophiles at first predominated. From 1884 the populists (see Populism, Western Ukrainian) assumed the leadership in Ukrainian public life. They founded a number of new organizations and published the periodical Bukovyna (1885–1918). Led by Stepan Smal-Stotsky, Yerotei Pihuliak, Omelian Popovych, and Mykola Vasylko, the Ukrainians of Bukovyna made important gains in the political, civic, economic, cultural, and religious fields.

Not until 1890 did Ukrainians win representation at the provincial diet and in the Vienna parliament, where their representatives from Bukovyna and Galicia formed the Ukrainian Club. After 1911 Ukrainians exerted greater influence in the administration of Bukovyna. By that year they had 16 representatives in the provincial diet. The vice-marshals of the diet were Stepan Smal-Stotsky (from 1904) and Rev Teofil Drachynsky (from 1911). At the turn of the century the populists split into various parties: the National Democratic party (led by Smal-Stotsky until 1911, then by Mykola Vasylko and Drachynsky), the Ukrainian Radical party (founded in 1906 and led by Teodot Halip and Ilko Popovych), and the Ukrainian Social Democratic party (led by Yosyp Bezpalko and Mykola Havryshchuk).

Cultural-educational work was carried on by the Ruska Besida in Bukovyna society, which had nine branches in various towns, 150 reading rooms in villages, and a membership of 13,000; by the Ukrainska Shkola society, and by the Sich societies (a sports and firefighting organization). In Chernivtsi the People's Home network was responsible for cultural work. The Selianska Kasa union of agricultural associations headed a system of savings and loan co-operatives of the Raiffeisen type. Ukrainian schools were well organized in Bukovyna; there were 216 elementary schools and 6 secondary schools (4 gymnasiums and 2 teachers' seminaries). At Chernivtsi University, which was founded in 1875 with German as the language of instruction, there were three chairs besides the chair in Ukrainian language and literature whose holder lectured in Ukrainian. Generally speaking, up to 1914 Bukovyna had the best Ukrainian schools and cultural-educational institutions of all the regions of Ukraine.

In the religious field the Orthodox Ukrainians of Bukovyna strove for equality with the Romanians. They achieved it in part on the eve of the First World War. The consistory was divided into two branches—Ukrainian and Romanian. A bishop was appointed for the Ukrainians (Taras Tyminsky); two Ukrainian chairs were established in the faculty of theology; and church publications appeared in Ukrainian. The Greek Catholic deanery of Chernivtsi was subordinated to the Lviv archeparchy from 1811 and from 1885 to the Stanyslaviv eparchy. The efforts of Ukrainians to divide Bukovyna into a Ukrainian- and a Romanian-governed section did not succeed. Ukrainian achievements were accompanied by friction with the Romanians, especially at the turn of the century. Rural overpopulation and difficult economic conditions forced many peasants to emigrate overseas (almost 50,000 left in 1891–1910) and led to peasant strikes in 1901–5 (see Peasant strikes in Galicia and Bukovyna).

During the First World War Bukovyna was a war zone and therefore suffered great losses. In 1915 Ukrainian representatives from Bukovyna and from Galicia organized the General Ukrainian Council in Vienna (with Mykola Vasylko as vice-president).

1918–40. On 25 October 1918 the Ukrainian Regional Committee, with Omelian Popovych as chairman, was established in Chernivtsi to represent the Ukrainian National Council in Bukovyna. This committee organized a massive public rally in Chernivtsi on 3 November to demand that Bukovyna be attached to Ukraine, and on 6 November it took power in the Ukrainian part of Bukovyna, including Chernivtsi. Romanian moderates, led by A. Onciul, accepted the division of Bukovyna into Ukrainian and Romanian sections, but Romanian conservatives under I. Flondor's leadership rejected this idea. On 11 November the Romanian army occupied Chernivtsi and all Bukovyna in spite of resistance from the Ukrainians. The General Congress of Bukovyna, which was hastily summoned by the Romanians, declared the unification of Bukovyna with Romania on 28 November. The Treaty of Saint-Germain, signed on 10 September 1919, recognized Romania's right to the part of Bukovyna settled by Romanians. On 10 August 1920 the Treaty of Sèvres ceded all of Bukovyna to Romania. Official representatives of the Western Ukrainian National Republic, the Ukrainian National Republic, and the Ukrainian SSR protested this action.

The Romanian government canceled all the autonomous powers of Bukovyna and turned it into an ordinary Romanian province. The Ukrainian school system was dismantled; Ukrainian cultural and civic life was restricted; and the Ukrainian church was persecuted (Romanian was introduced into the liturgy). In 1918–28 and 1937–40 Bukovyna found itself in a state of siege. Ukrainians were particularly oppressed when the Liberal party was in power, and they made few gains when the National Peasant party took office. In the 1920s the Ukrainian section of the Social Democratic Party of Bukovyna (led by Vasyl Rusnak) became active. The left wing of the party (under Serhii Kaniuk) became the Communist Party of Bukovyna. In time the Ukrainian National party (1928–38), under the leadership of Volodymyr Zalozetsky-Sas, Vasyl Dutchak, and Yurii Serbyniuk, became the legal political representative of the Ukrainian population. Having reached an understanding with Romanian political parties, the Ukrainian National party won several seats in the Romanian parliament. When Romania became an authoritarian state in 1938, the position of Ukrainians in Bukovyna grew even worse. In the 1930s an underground nationalist movement led by Orest Zybachynsky and Denys Kvitkovsky gained strength. To counteract it, the Romanian government staged two political trials in 1937.

In spite of government persecution, Ukrainian organizations—such as the People's Home in Chernivtsi (headed by O. Kupchanko); the Ukrainska Shkola educational society (led by A. Kyryliv and Teofil Bryndzan); the musical societies Bukovynskyi Kobzar (Chernivtsi 1920–40) and the Ukrainian Male Choir; the Women's Hromada in Bukovyna (headed by Olha Huzar); the student societies Zaporozhe, Chornomore, and Zalizniak; and the Ukrainian Theater (headed by Sydir Terletsky and Ivan Dutka) - continued their cultural activities. The publication of the daily Chas (Chernivtsi) by Lev Kohut, several weeklies—Khliborobs’ka pravda, Ridnyi krai (Chernivtsi), Rada (Chernivtsi), and Samostiinist’—and the journal Samostiina dumka was an important achievement.

Under Romanian domination there were 155 Ukrainian Orthodox parishes (out of a total of 310), 135 Ukrainian priests, and 330,000 church members in Bukovyna. The Greek Catholic church had 17 parishes and 17 priests. In 1923–30 it constituted the Bukovynian apostolic administration with its center in Seret. Then it became a general vicariate subordinated to the Romanian diocese of Baia Mare.

1940–5. On 28 June 1940 the Romanians withdrew from the Ukrainian part of Bukovyna in response to an ultimatum from the USSR, and Soviet troops moved in. By decision of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on 2 August, northern Bukovyna, together with northern Bessarabia and a small part of old Romania containing the town of Hertsa, became Chernivtsi oblast. During the year-long Soviet occupation some radical changes took place in Bukovyna: private property was nationalized; farms were partly collectivized; and education was Ukrainianized. At the same time all Ukrainian organizations were disbanded, and many publicly active Ukrainians were either killed or exiled. A significant part of the Ukrainian intelligentsia had emigrated to Romania or Germany when the Soviet occupation began. When the German-Soviet war broke out and the Soviet troops retreated from Bukovyna, Ukrainians tried to establish their own local government, but they could not withstand the advance of the Romanian army. In July 1941 almost 1,000 Bukovynians fled to Galicia, where they formed the Bukovynian Battalion of 1941 under the leadership of Petro Voinovsky. This company joined the OUN expeditionary groups of the OUN (Melnyk faction) and reached Kyiv. In 1941–4 the Romanians set up a military dictatorship in Bukovyna (which was turned into a Generalgouvernement), established concentration camps, put prominent Ukrainians (Olha Huzar, M. Zybachynsky, and others) on trial, prohibited any kind of civic and cultural work, and introduced total Romanianization. At this time partisan groups sprang up in the mountains of Bukovyna forming the Bukovynian-Ukrainian Self-Defense Army. Under V. Luhovy's leadership these units fought the Romanians and, in 1944, the Soviets.

In March 1944 Soviet troops occupied northern Bukovyna for the second time. The Paris Peace Treaty of 1947 between the Allies and the Romanians (see Paris Peace Treaties of 1947) recognized the Soviet-Romanian border that had been established in 28 June 1940. The Soviet government created in Bukovyna the same conditions of life as in the Ukrainian SSR.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kaindl, R.F. Geschichte der Bukowina, 3 vols (Chernivtsi 1896–1903)

Smal’-Stots’kyi, S. Bukovyns’ka Rus’ (Chernivtsi 1897)

Die österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild. Bukowina (Vienna 1899)

Korduba, M. Iliustrovana istoriia Bukovyny (Chernivtsi 1901)

Nistor, I. Românii şi Rutenii în Bucowina (Bucharest 1915)

Korduba, M. ‘Perevorot na Bukovyni,' LNV, 1923, nos 10-12

Piddubnyi, H. Bukovyna, ïï mynule i suchasne (Kharkiv 1928)

Popovych, O. Vidrodzhennia Bukovyny (Lviv 1933)

Kvitkovs’kyi, D.; Bryndzan, T.; Zhukovs'kyi, A. (eds). Bukovyna, ïï mynule i suchasne (Paris-Philadelphia-Detroit 1956)

Borot’ba trudiashchykh Bukovyny za sotsial’ne ta natsional’ne vyzvolennia i vozz’iednannia z Ukraïns’koiu RSR, 1917–1941: Dokumenty i materialy (Chernivtsi 1958)

Hubar, O.; Dikhtiar, S.; Romanets', O.; Chernets', L. Literaturna Bukovyna (Kyiv 1966)

Hryhorenko, O. Bukovyna vchora i s’ohodni (Kyiv 1967)

Radians’ka Bukovyna 1940–1945: Dokumenty i materialy (Kyiv 1967)

Demochko, K. Mystets’ka Bukovyna (Kyiv 1968)

Tymoshchuk, B. Pivnichna Bukovyna–zemlia slov’ians’ka (Uzhhorod 1968)

Kurylo, V.; Lishchenko, M.; Romanets', O.; Syrota, N.; Tymoshchuk, B. Pivnichna Bukovyna, ïï mynule i suchasne (Uzhhorod 1969)

Nowosiwsky, I. Bukovinian Ukrainians (New York 1970)

Mynule i suchasne Pivnichnoï Bukovyny, 3 vols (Kyiv 1972–4)

Karpenko, Iu. Toponomiia Bukovyny (Kyiv 1973)

Shevchenko, F.; et al (eds). Narysy z istoriï Pivnichnoï Bukovyny (Kyiv 1980)

Tymoshchuk, V. Davnorus’ka Bukovyna (x-persha polovyna XIV st.) (Kyiv 1981)

Kukurudziak, M. Robitnychyi rukh na Pivnichnii Bukovyni naprykintsi XIX-na pochatku XX stolittia (Lviv 1982)

Himka, J-P. Galicia and Bukovina: A Research Handbook about Western Ukraine. [Alberta] Historic Sites Service Occasional Report No 20 (Edmonton 1990)

Zhukovs’kyi, A. Istoriia Bukovyny (Chernivtsi 1991)

Turczynski, E. Geschichte der Bukowina in der Neuzeit: Zur Sozial- und Kulturgeschichte einer mitteleuropäisch grepägten Landschaft (Wiesbaden 1993)

Kostyshyn, S. (ed). Bukovyna: Istorychnyi narys (Chernivtsi 1998)

Dobrzhans’kyi, O. Natsional’nyi ruk ukraïntsiv Bukovyny druhoï polovyny XIX–pochatku XX st. (Chernivtsi 1999)

Kozholianko, H. Etnohrafiia Bukovyny. Tom 1 (Chernivtsi 1999)

Pavliuk, O. Bukovyna: Vyznachni postati, 1774–1918: Biohrafichnyi dovidnyk (Chernivtsi 2000)

Nykyforak, M. Derzhavnyi lad i pravo na Bukovyni v 1774–1918 rr. (Chernivtsi 2001)

Skoreiko, H. Naselennia Bukovyny za avstriis’kymy uriadovymy perepysamy druhoï polovyny XIX–pochatku XX st.: Istoryko-demohrafichnyi narys (Chernivtsi 2002)

Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Arkadii Zhukovsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984).]

.jpg)

.jpg)