Podilia

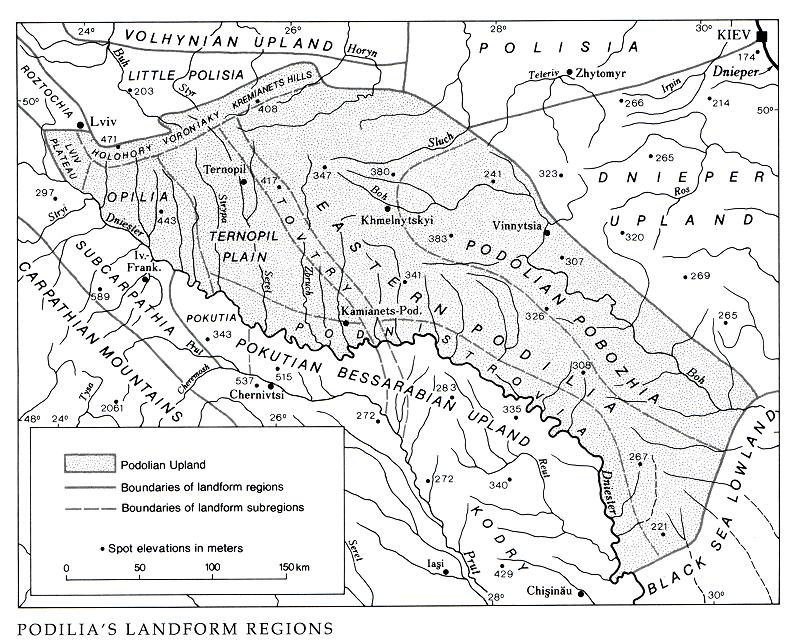

Podilia (Podolia) [Поділля (Подоля)]. (Map: Podilia; Detailed map: Podilia.) A historical-geographical upland region of southwestern Ukraine, consisting of the western part of the forest-steppe belt. Podilia is bounded in the southwest by the Dnister River, beyond which lie the Pokutian-Bessarabian Upland and Subcarpathia. To the north it overlaps with the historical region of Volhynia, where the Podolian Upland descends to Little Polisia and Polisia. In the west it is bounded by the Vereshchytsia River, beyond which lies the Sian Lowland. To the east Podilia passes imperceptibly into the Dnipro Upland, with the Boh River serving as part of the demarcation line, and in the southeast it descends gradually toward the Black Sea Lowland and is delimited by the Yahorlyk River and the Kodyma River. The Podilia region thus coincides with the Podolian Upland, which occupies an area of approx 60,000 sq km.

The name Podilia has been known since the mid-14th century, but it did not originally refer to the aforementioned geographical region or to a single administrative-territorial unit. It usually meant the land between two left-bank tributaries of the Dnister River, the Strypa River in the west and the Murafa River in the southeast, and the Boh River in the east, an area of approx 40,000 sq km. Podilia voivodeship, established at the beginning of the 15th century, encompassed only the central part of Podilia. During the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Podilia was understood to include not only Podilia voivodeship but also Bratslav voivodeship and the northeastern part of Rus’ voivodeship. Its southern and southeastern areas, however, remained unsettled, and the border between the Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire marked by the Kodyma River and the Syniukha River was only conventional. In the 19th century eastern Podilia often meant Podilia gubernia, which consisted approximately of the former Podilia voivodeship and Bratslav voivodeship, whereas western Podilia meant the eastern part of Galicia. At the beginning of the 20th century the name Podilia was applied to lands as far west as the Zolota Lypa River. Today Podilia encompasses Ternopil oblast (although the Kremenets area historically belonged to Volhynia), almost the whole of Khmelnytskyi oblast and Vinnytsia oblast, and small parts of Lviv oblast and Ivano-Frankivsk oblast.

The history of Podilia was strongly influenced by its proximity to the steppe, for centuries the source of nomadic raids. For a long time much of Podilia was under the control of the Pechenegs, Cumans, and Tatars. From the mid-15th century Podilia was the favorite target of Tatar raids. When they diminished, the fertile region attracted Polish colonists from the northwest, who filled the political power vacuum.

Physical geography. Structurally, Podilia is connected to the following tectonic regions: the western slope of the Ukrainian Crystalline Shield, the Volhynia-Podilia Plate, and the Galician-Volhynian Depression. The Precambrian foundation of Podilia is exposed in the east by the Boh River, which has eroded the thin Tertiary deposits. To the southwest the shield dips (down to 6,000 m) below Paleozoic deposits of Silurian limestones and sandstones and Devonian red Terebovlia sandstones, marls, and dolomites, which constitute the bedrock of ‘Paleozoic Podilia’ between the Zolota Lypa River and the Murafa River. Jurassic deposits appear on the surface only in western Podilia along the Dnister River. Thick deposits of Cretaceous chalk and marl (exposed in western Podilia and in deep ravines) and of middle Miocene sands, sandstones, marls, and limestones are found throughout Podilia. They are covered with layers of Quaternary clays, silts, and loess (up to 20 m thick).

Podilia is a plateau dissected by valleys that has an elevation of 300–400 m above sea level. The region may be differentiated into a number of landscapes according to geological formation, elevation, distance from the baseline of erosion (for most of Podilia, the Dnister River), and tectonic movement. The highest part of Podilia is its northern rim, known as the Holohory-Kremenets Ridge, approximately 350–470 m above sea level (Kamula, 473 m). From there elevations drop sharply (150–200 m) to Little Polisia. The western part of Podilia, west of the upper reaches of the Zolota Lypa River, the Koropets River, and the mouth of the Strypa River, is known as Opilia Upland. With elevations ranging from 350 to 470 m, Opilia has a foundation of soft gray Cretaceous marl, which was eroded vertically and laterally by rivers to produce a hilly landscape. East of Opilia, Podilia is divided from the northwest to the southeast by a low ridge, the Tovtry, into western and eastern Podilia. Western Podilia consists of the Ternopil Plain in the north and the gullied fringe along the Dnister River in the south. The Ternopil Plain is characterized by relatively flat interfluves and broad, often swampy river valleys (now containing many artificial ponds) in the soft chalk bedrock. Farther south, as the rivers cut into the Devonian sandstones and then into the Silurian shales, their profile becomes steeper, white water and waterfalls appear, and the valleys turn into deep ravines. The deepest and most spectacular ravine is that of the Dnister: it is carved approximately 100–150 m below the adjacent uplands, sometimes in a straight line but more frequently in tightly twisting meanders. The upland between the ravines is a gently undulating plateau. Wherever chalk deposits come close to the surface along the Dnister, karst phenomena abound—sink holes, temporarily or permanently filled with water, and caves, notably at Bilche Zolote and Kryvche.

The mostly featureless plain of Podilia proper is interrupted by the Tovtry or Medobory. East of them lies eastern Podilia, of which the northern and southern parts are different. The northern part, which encompasses the headwaters of the tributaries of the Prypiat River and the Dnister River as well as the drainage basin of the upper Boh River, resembles the Ternopil Plain. Reaching 360 m above sea level, the upland consists of broad intervalley crests rising slightly above broad, often swampy and ponded valleys. The highest elevations occur along the watersheds between the Prypiat drainage basin to the north and the Dnister and the Boh drainage basins to the south and between the Boh and the Dnister drainage basins. The southern fringe of eastern Podilia is a continuation of the Dnister region, a zone of ravines and gullies flanking the northern bank of the Dnister River. Near Yampil (Vinnytsia oblast) the deep Dnister Gorge exposes the granite foundation of the Ukrainian Crystalline Shield.

The easternmost part of Podilia, often called the Podolian Pobozhia region, is a transition zone between Podilia and the Dnipro Upland, from a plateau to a granitic landscape. Elevations there reach 300 m above sea level, and the rivers cut deep ravines and valleys (500–570 m), especially to the south.

The climate of Podilia is temperate continental. The continentality increases from the northwest to the southeast, as is evident in the increasing annual temperature range, from 23°C in Opilia Upland to 25.5°C in the east. The number of days with temperatures above 15°C also increases, from 100 in the west to 120 in the southeast. The greatest precipitation occurs in Opilia and along the northern rim, where it exceeds 700 mm per year, and along the Tovtry, and the lowest, along the southern slopes, where it is approx 475 mm. Most of the precipitation occurs in the summer, often in the form of downpours. There is a marked difference in temperature between northern and southern Podilia: whereas in Ternopil the average January temperature is –5.5°C, in Zalishchyky (100 km south, on the Dnister River), it is –4.7°C; and the corresponding average July temperatures are 18.3°C and 19.4°C. The growing season is 203 and 215 days. The warmest areas are the sheltered, south-facing slopes in the Dnister Gorge.

The river network of Podilia is fairly dense. The densest drainage network consists of the numerous south-flowing streams that empty into the Dnister River. The drainage system of the Boh River Basin and the network contributing to the Prypiat River are less dense. Only the Dnister River can be navigated by shallow-water rivercraft. The hydroelectric potential of the rivers has not been fully exploited. In the south the rivers provide some water for irrigation.

The most common soils in Podilia are (1) the moderately fertile gray and light gray podzolized soils on loess, mostly in the southeast, (2) the hilly, fertile degraded chernozems and dark gray podzolized soils on loess, mostly in the west, and (3) the highly fertile, low-humus typical chernozems on loess, mostly in the northeast. The soil types are frequently interspersed among one another, especially in the deeply sculpted and therefore highly varied Dnister region.

The vegetation of Podilia is influenced by its transitional location, between the Carpathian Mountains in the southwest, Polisia in the north, and the steppe in the south, and by its special morphology and soils. Most of Podilia belongs to the forest-steppe belt. Forests cover less than 10 percent of the region: substantial tracts are found only in the Tovtry, in the Dnister Gorge and its tributaries, and along the Boh River. The distribution limits of a number of eastern and western plant species run through Podilia. The eastern limits of the beech, yew, fir, and spruce lie in western Podilia. The most common trees found in central and eastern Podilia, therefore, are the oak and hornbeam, with admixtures of ash, maple, elm, and sour cherry. By human intervention mixed oak groves are being replaced by uniform woods of hornbeam. The underbrush is dominated by hazel, snowball tree, buckthorn, and red bilberry. Some of the eastern species, such as the common maple, do not penetrate farther west. A peculiar vegetation complex is found in the ravines of Podilia and on the rock outcrops and detritus. The meadow steppes of Podilia are fully cultivated. At the end of the 19th century, the last remnant of the steppe, between the Seret River and the Strypa River, was known as the Pantalykha Steppe. It contained a great variety of herbs and broad-leaved grasses typical of the meadow-steppe, including the lungwort, nettle, and madder.

The transitional nature of Podilia also determines its fauna. The more densely forested western part is inhabited by the fox, the rabbit, two kinds of marten, the Eurasian red squirrel, and the now-rare wolf and wild boar. Valuable fur-bearing animals, such as the mink and European otter, lived along the rivers. Among forest birds the goldeneye, and in the meadows the partridge and quail, were common. In western Podilia near Subcarpathia the typical animals were the ermine, weasel, wildcat, wild boar, and muskrat; among the ungulates, the chamois and deer; in wet areas, the salamander; and among the birds, the bullfinch. The peripheral location of western Podilia was suited to some West European fauna, including certain varieties of bat, vole, and insect. At the same time some steppe fauna, such as the mole-rat, polecat, field vole, gopher, steppe lark, black-headed yellowhammer, and, less frequently, the great bustard, the steppe snake, the green lizard, the boa, and a variety of mollusks, insects (including beetles), and spiders, intruded into Podilia. In the southeast most of the steppe fauna was adapted to wide open spaces and a rather dry climate. As farming spread, so did various mice, field voles, and other small rodents, as well as various insect pests.

Prehistory. Some of the oldest traces of human habitation in Ukraine are found in Podilia and Transcarpathia. Ancient stone and flint tools (over 900,000 years old) have been found at the Medzhybizh archeological site. The site of Luka-Vrublivetska (400,000–100,000 years ago) also belongs to the Acheulean culture of the Lower Paleolithic Period. From that time Podilia was continuously inhabited, by Neanderthal humans of the Mousterian culture of the Lower Paleolithic Period, by Cro-Magnon humans of the Aurignacian, Solutrean, and Magdalenian cultures of the Upper Paleolithic Period, and finally by humans of the Campignian culture of the Mesolithic Period. During the Neolithic Period Podilia was populated by communities of the Boh-Dnister culture and Linear Pottery culture, and during the Eneolithic Period it was almost entirely the territory of the Trypillia culture.

History. According to Herodotus the forest-steppe belt, including Podilia, was inhabited (during the Iron Age) by Scythian farmers, whose way of life differed from that of Scythian nomads in the steppe. Beginning in the 2nd century BC the Scythian nomads were displaced by the Sarmatians, who often raided the Podolian settlements. At the end of the 1st millennium BC the warlike Venedi and the Celtic Bastarnae crossed Podilia, but neither left a significant cultural impact on its population, which continued to grow grain and sell its surplus to the Greek colonies on the Black Sea (see Ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast) and the Roman merchants in Dacia. From the 1st to the 4th century the Cherniakhiv culture prevailed in the Ukrainian forest-steppe belt, including Podilia. The early Slavic tribes, known as the Antes in Byzantine sources, were the most likely bearers of that culture. They survived the invasion of the Goths (4th century) and the Huns (5th century) and finally collapsed under the onslaught of the Avars (7th century).

According to the Primary Chronicle Podilia was settled by several Ukrainian tribes: the Ulychians (along the Boh River), the Tivertsians (along the Middle and Lower Dnister River), the White Croatians (in Subcarpathia, in the southwest), and the Dulibians (in the northwest along the Buh River). During the reign of Prince Oleh and Prince Ihor Podilia became part of the Kyivan Rus’ state. At the same time the southern part of Podilia was seized by the Pechenegs, who forced the Ulychians and the Tivertsians to move north. As the power of Kyivan Rus’ waned, it lost interest in eastern Podilia, and the region became a marchland of Galicia. The Tatar Burundai's campaign against Galicia (1259) sealed Podilia's fate for a century. Western Podilia along with Galicia remained under the Romanovych dynasty, and middle and eastern Podilia was administered directly by the Tatars of the Golden Horde.

Under Lithuanian-Polish rule. The political situation changed radically in the mid-14th century. The Lithuanian grand duke Algirdas defeated the Tatars at Syni Vody (1363), captured middle Podilia, and granted it as a fiefdom to his relatives, the Koriiatovych family. The new masters built fortified towns, including Smotrych, Bakota, and Kamianets-Podilskyi. After the death of the last Galician prince, Yurii II Boleslav, Casimir III the Great annexed Galicia (1349) and western Podilia (1366), which was integrated with Poland in 1387. The conflict between Poland and the Lithuanian grand duke Vytautas the Great over middle Podilia and its principal town, Kamianets-Podilskyi, led to the expulsion of Fedir Koriiatovych in 1393. Vytautas kept eastern Podilia (the Bratslav and Vinnytsia regions) and ceded middle Podilia to Jagiełło of Poland (1395) but later reclaimed it (1411). After the duke's death the pro-Polish gentry of middle Podilia declared it Polish and turned it into Podilia voivodeship. Western Podilia was incorporated into Rus’ voivodeship.

Polonization in Podilia was promoted not only by the Polish administration but also by the Roman Catholic church, which established a diocese in Kamianets-Podilskyi. Ukrainians became a minority among the nobility, and eventually only the petty gentry, who served in the borderland forts, remained Ukrainian. Meanwhile the population of Podilia grew, because the fertile soil and the relatively undemanding corvée attracted peasants. The towns attracted mainly Poles and Jews as well as some Germans and Armenians.

After 1430 only eastern Podilia, with the towns of Bratslav and Vinnytsia, remained under Lithuania. The Poles made every effort to annex that part and succeeded in doing so in the Union of Lublin (1569). From then, Polish magnates swarmed into eastern Podilia, where they set up enormous estates and seized key administrative positions. Eastern Podilia became Bratslav voivodeship.

Raids by the Crimean Tatars, which began in the second half of the 15th century, crippled Podilia's developing economy. The Crimean Horde regarded Podilia not only as an object of prey but also as a gateway, via the Kuchmanskyi Route and the Black Route, to the more populous lands of Volhynia, Galicia, the Kholm region, and Poland proper. At the beginning of the 16th century southeastern Podilia became deserted, and the advances in colonization made during the 15th century were lost. Colonization resumed in the mid-16th century. As the demand for grain rose in Western Europe, the large landowners in Podilia developed commercial farming and raised the corvée obligations of the peasants. The Cossacks and the alienated Ukrainian burghers came to the defense of the peasantry. The Cossack Hetman state set up by Bohdan Khmelnytsky encompassed only a part of Podilia; namely, Bratslav regiment and Vinnytsia regiment. When Poland and Muscovy divided Ukraine into Right-Bank Ukraine and Left-Bank Ukraine in 1667, Podilia became part of Right-Bank Ukraine. Hetman Petro Doroshenko's attempt to reunify Left-Bank and Right-Bank Ukraine with Turkey's help ended with Turkey's annexation of Podilia voivodeship (1672). Although Doroshenko retained control of the Bratslav region, continuous warfare, Tatar raids, and Turkish oppression caused mass migration into Left-Bank Ukraine. In 1699 Podilia was taken by Poland. In 1712, after an unsuccessful rebellion, the Cossack regiments were disbanded. In the first half of the 18th century Podilia was colonized intensively. Peasants, mostly from Rus’ voivodeship and Volhynia but also from Left-Bank Ukraine, Moldavia, and Poland proper, poured into the depopulated territory. By the mid-18th century Podilia voivodeship had the highest population density in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Although Tatar raids had ceased, there was no lasting peace in the region. National and religious oppression along with increasing corvée provoked the so-called haidamaka uprisings against the Polish nobility. Centered in the southern part of the Kyiv region and the southeastern part of the Bratslav region, they encompassed all of eastern Podilia.

The modern period. With the First Partition of Poland (1772) western Podilia, east to the Zbruch River, was annexed by Austria, and with the Second Partition (1793) eastern Podilia was transferred to Russia. A portion of Austrian-ruled Podilia (Ternopil and Zalishchyky counties) was held briefly (1809–15) by Russia. After the division each part of Podilia developed differently. In eastern Podilia the intensification of serfdom gave rise to peasant discontent and Ustym Karmaliuk's revolts. Kamianets-Podilskyi became the administrative center of Podilia gubernia and Podilia eparchy. The Ukrainian national and cultural movement developed slowly in Podilia, mainly at the end of the 19th century. Its centers were Kamianets-Podilskyi and Vinnytsia. Social and economic progress in the gubernia was also slow: a zemstvo was set up only in 1911.

In western Podilia, as in all Galicia, the Polish population continued to increase and to dominate the administration of the land. Nevertheless western Podilia, along with the rest of Galicia and Bukovyna, became the base of the modern Ukrainian national and political movement. Because of their proximity to Lviv the towns of western Podilia (Ternopil, Berezhany, Buchach, and Chortkiv) did not develop into great cultural and political centers.

During the Ukrainian struggle for independence (1917–20) Podilia was a battleground for the Ukrainian, Polish, Russian, and Bolshevik armies. In the interwar period western Podilia was ruled by Poland and was known as Ternopil voivodeship. Eastern Podilia, meanwhile, was part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. After the Second World War all Podilia became part of the Ukrainian SSR. It consisted of three oblasts: Ternopil oblast, Khmelnytskyi oblast (formerly Proskuriv oblast), and Vinnytsia oblast. It remains one of the most agricultural and least industrialized regions of Ukraine.

Population. Since the middle of the 18th century Podilia, together with Pokutia and Subcarpathia, has been the most densely populated part of Ukraine. Today those regions as well as lowland Transcarpathia have the highest rural population densities. In 1860 western Podilia was settled more densely (63 persons/sq km) than eastern Podilia (43 persons/sq km), but eventually the gap narrowed (in 1897 the figures were 96 and 75, and in 1932, 99 and 98). With a low level of urbanization (approx 10 percent) Podilia, especially its western part, was one of the most land-hungry regions of Ukraine. The peasants of western Podilia responded to the problem of employment with mass emigration (over 200,000 people between 1890 and 1913) to the New World and a reduced rate of natural increase. Emigration from eastern Podilia was smaller, partly because there was local employment in the sugar industry. Sizable population losses occurred in eastern Podilia during collectivization and in all of Podilia during the Second World War (1940–6). By 1959 the population of Podilia was still 14.5 percent smaller than in 1926. The process of urbanization was slower there than anywhere else in Ukraine. The changes in the composition and density of the population in the three Podilia oblasts (Ternopil oblast, Khmelnytskyi oblast, and Vinnytsia oblast) are given in Table 1. Podilia's migration balance has continued to be negative. In the six years from 1963 to 1968 the region's natural increase was 210,000, and its net population increase only 20,000. Despite a positive natural increase the population of Podilia has declined since 1970. Population distribution, expressed as rural population density, does not vary greatly from one raion to another. Rural population densities range from 50 to 80 persons per sq km but usually lie between 60 and 70.

The settlements in Podilia are concentrated along rivers in the valleys or wide canyons, and the interfluves of the plateau are occupied by cropland. Only where the ravines are too narrow to accommodate them are villages built along the rim of the plateau.

Before industries developed, the towns of Podilia were administrative and trading centers. The smaller towns engaged in local trade and services for farming. Now all the more important towns of Podilia have industries, but in comparison to other parts of Ukraine they are relatively small. In 2001 only four cities had over 100,000 residents: Vinnytsia (357,000), Khmelnytskyi (254,000), Ternopil (228,000), and Kamianets-Podilskyi (100,000). In Opilia Upland, the westernmost part of Podilia, the smaller towns (2001 population estimates) include Berezhany (18,800), Bibrka (3,900), Khodoriv (10,200), Monastyryska (6,200), Peremyshliany (7,500), Pidhaitsi (6,100), and Rohatyn (8,800). The southwestern gullied part includes the towns of Borshchiv (11,200), Buchach (12,500), Chortkiv (28,800), Kopychyntsi (7,000), Terebovlia (13,600), and Zalishchyky (9,700), and the flat northern part of western Podilia includes Ternopil, Zalistsi (2,800), Zbarazh (13, 000), and Zboriv (7,300). On the northwestern rim are Brody (30,000), Kremenets (23,300), and Zolochiv (23,000). The more important economic and cultural centers are Ternopil, Berezhany, Buchach, Chortkiv, and Kremenets. In eastern Podilia, along the Dnister River, the main center is Kamianets-Podilskyi; it is followed by Mohyliv-Podilskyi (32,500), Yampil (Vinnytsia oblast) (11,700), and Rybnytsia (57,200, Rîbniţa in Moldova). The northern plain of eastern Podilia is dominated by Khmelnytskyi and, to a lesser extent, by Starokostiantyniv (35,200). On the northern border with Volhynia are Iziaslav (18,400), the rail hub Shepetivka (47,900), and Polonne (21,200). Along the Boh River Vinnytsia predominates among the small towns, such as Letychiv (or Liatychiv, 11,000), Lityn (6,900), Tulchyn (16,100), Bratslav (6,000), Bar (17,200), Khmilnyk (28,100), Derazhnia (10,400), Medzhybizh (1,700), the important railway hub Zhmerynka (35,500), and a smaller hub, Vapniarka (8,200). To the southeast are located Bershad (13,300), Balta (19,700, although in the mid-19th century it was, after Kamianets-Podilskyi, the second-largest town in Podilia), Kotovsk (40,600), and Ananiv (9,300).

In past centuries there was a steady flow of Poles (particularly in the first half of the 18th century) and Jews into Podilia. The Jews constituted a majority in most of the towns. The Poles were concentrated in the north, on both sides of the Zbruch River. Some of the Poles living among the Ukrainians became linguistically assimilated and retained only their Roman Catholic faith.

During the 19th and 20th centuries interethnic relations evolved very differently in western (under Austria and Poland) and eastern Podilia (under Russia and in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic). In the eastern region the Polish and Roman Catholic element was deprived of government support and reinforcements from the west, and began to succumb to Ukrainization and, in the cities, to a degree of Russification. Most Roman Catholics were Ukrainian-speaking (in 1926, 50 percent; by 1959, up to 85 percent). The proportion of Jews in the population grew until the end of the 19th century and then began to decline. Russians were a small minority (7 percent in towns and cities, 1 percent in the villages). In southern Podilia along the Dnister (within today's Moldova) some 50,000 Moldavians were concentrated in one area. As a result of the Second World War the Jewish population fell drastically, the Polish element declined, and the Russian element increased substantially (see Table 2).

In western Podilia for two centuries, particularly after the mid-19th century, the proportion of Poles increased at the expense of Ukrainians. There was a continuous flow of Poles from the western (Polish) part of Galicia to the towns dominated by a Polish administration and to farmlands sold off by Polish landowners. Emigration to the New World, which drew proportionally more Ukrainians than Poles, and the Polonization of Ukrainians through conversion from the Uniate (Greek Catholic) faith to Roman Catholicism were less significant. The changes in the composition of the population according to religion are shown in Table 3. The greatest loss of Ukrainians occurred in a zone extending from Lviv to the Zbruch River, where the Poles and the Ukrainian-speaking Roman Catholics represented about one-third of the population. Most of the residents in the towns of western Podilia were Jewish; in number they were followed by Poles or Ukrainians. By contrast, in eastern Podilia one-half of the urban population was Ukrainian, over one-third was Jewish, and an insignificant proportion was Polish. As a result of the Second World War the ethnic composition of western Podilia changed dramatically, and today it resembles that of eastern Podilia. In Ternopil oblast the ethnic composition for 1959 and 1979 indicates the persistent growth of the Ukrainian element: Ukrainians made up 90.2 and 96.6 percent, Russians, 2.5 and 2.2 percent, Poles, 2.2 and 0.9 percent, and Jews and others, 5.1 and 0.3 percent.

Economy. Agriculture has always been the foundation of the Podilian economy. In the 1920s nearly 80 percent of the population was employed in farming and less than 10 percent worked in the trades and industry. Until the mid-1930s only the food industry, consisting of the sugar industry and liquor and spirits distilling, was developed. The sugar industry was limited to eastern Podilia, because Czech competition and Polish competition after the war blocked its growth in western Podilia. During the Soviet period industrializaion was speeded up, but Podilia remains one of the least industrialized regions in Ukraine.

Agriculture. Most of the land in Podilia is tilled (72 percent). The rest is devoted to hayfields, meadows and pastures (7 percent), orchards and berry plantings (3 percent), and forests (nearly 15 percent). The sown area in the three oblasts of Podilia in 1987 totaled 4,187,000 ha, of which 2,014,000 ha (48.1 percent) were devoted to grain. As in the rest of Ukraine the share of the grain area has declined, from about 75 percent in the 1920s, and the share of land given to industrial crops (especially in Galician Podilia) and fodder crops has increased. Sugar beet is Podilia's predominant industrial crop; it occupies 489,000 ha (88 percent of all industrial-crop land, or 12 percent of all crop land) and represents 23 percent of the sugar-beet area in Ukraine. The sugar-beet area has increased by almost two and a half times since 1940 (especially in western Podilia). Other industrial crops include sunflower (50,000 ha, mostly in Vinnytsia oblast), rape, tobacco, hemp, aromatic oil seeds, and medicinal plants. The area of feed crops has increased by 2.45 times since 1940; it amounted to some 1,305,000 ha, or 31.2 percent of the sown area, in 1987. Besides perennial and annual grasses, corn and other feed crops are raised. The sown area in potatoes and vegetables has declined from 424,000 ha in 1940 to 314,000 ha (7.5 percent of the sown area), a reflection of the falling demand for potatoes. After Southern Ukraine Podilia is the second most important fruit-farming region in Ukraine. Orchards in Podilia occupy over 200,000 ha, and vineyards, over 5,000 ha. The most common fruit trees are apple, plum, pear, sour cherry, morello cherry, apricot, peach, and walnut.

In animal husbandry the leading branches are dairy and beef farming and hog raising (see Table 4).

Podilia produces commercial surpluses of sugar beets, which are processed locally, fruits, and animal products. There is little regional specialization in agriculture, but the region south of Ternopil is known for its tobacco, and the regions along the Dnister River in eastern Podilia, to the south of Khmelnytskyi and to the southwest of Vinnytsia, are known for their fruits and vegetables.

Industry. Podilia lags considerably behind other parts of Ukraine in industrial development. Its main industry is food processing, which accounts for about 60 percent of the value of its industrial output; food processing is followed by machine building and the metalworking industry (15 percent), light industry (13 percent), and the building-materials industry (6 percent). The dominant branch of the food industry in Podilia is sugar refining (39 enterprises in Vinnytsia oblast alone); in 1987 that branch produced some 2.1 million t, or 28 percent of Ukraine's output of sugar. Liquor and spirits distilling is another important branch. Its raw materials are molasses (a by-product of the sugar industry), potatoes, and grain. Over 30 enterprises in the region produce alcohol. Their subsidiary operations include the production of feed yeast and vitamins. The largest distilleries are located in Bar and Kalynivka, in Vinnytsia oblast. The meat-processing industry is highly developed. Large meat packing plants are located in the three oblast centers. The dairy industry, which produces 42,000 t of butter per year (14 percent of Ukraine's total), is widely distributed. Its largest plant is in Horodok (Khmelnytskyi oblast). The largest urban (fluid milk) dairies are located in the oblast centers. Podilia contributes about 12 percent of Ukraine's canned fruits and vegetables. Oil pressing, flour milling, baking, confectionery manufacturing, brewing, and tobacco processing are mostly of regional or local significance.

Machine building and the metalworking industry arose in Podilia mostly in the 1950s and 1960s, along with related electrotechnical and chemical industries, and continue to grow in importance. Their main products are electrotechnical equipment, tractor assemblies and bearings, equipment for sugar refineries, transformer substation equipment, foundry equipment, and sheet-metal presses, tractor parts, electrical equipment, and agricultural machinery. The Vinnytsia Chemical Plant, which produced granulated superphosphate with manganese, was one of the largest fertilizer plants in the USSR. Podilia's light industry manufactures textiles, garments, and footwear. Its textile plants produce nearly 12 percent of the cotton cloth and 7 percent of the woolen cloth manufactured in Ukraine.

The building-materials industry includes the quarrying and finishing of granite and marble blocks, the mining and processing of limestone and chalk, brick-making, and tile manufacturing. Wood, mostly from Polisia, is used to make cellulose and paper in Poninka and paper in Slavuta, Polonne, and Rososha. Altogether the industry contributes nearly 23 percent of Ukraine's paper production.

The fuel and power industries of Podilia depend on coal, petroleum products, and natural gas brought in from the Donbas, Subcarpathia, and the Shebelynka gas field respectively. Electricity is generated principally at small thermal stations in Vinnytsia, Mohyliv-Podilskyi, Khmelnytskyi, Kamianets-Podilskyi, Shepetivka, Ternopil, and Kremenets, but their output has not met the needs of the region. It is supplemented by the new Ladyzhyn thermal-electric station on the Boh River, the Dnister Hydroelectric Station, and the Khmelnytskyi Nuclear Power Station. Most of the power from Ladyzhyn and the other new generating stations is slated for export to Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria.

Transport. Railways, which carry up to nine-tenths of the freight, are Podilia's most important means of transportation. Podilia has 2,542 km of track, about 11.5 percent of Ukraine's network, and a density of 42 km per 1,000 sq km, or 112 percent of the mean density of Ukraine. A three-pronged trunk line forms the skeleton of the railway system: it joins Lviv with Odesa through Ternopil and Khmelnytskyi and branches off at Zhmerynka through Vinnytsia to Kyiv. The other major lines that pass through Podilia and are connected to the trunk are: Zhmerynka–Mohyliv-Podilskyi–Chernivtsi, Koziatyn–Shepetivka–Rivne, Shepetivka–Ternopil–Chortkiv–Chernivtsi, and Korosten–Shepetivka–Khmelnytskyi–Kamianets-Podilskyi. The most important railroad junctions are Zhmerynka, Koziatyn, Shepetivka, and Vapniarka as well as the major cities of Ternopil, Khmelnytskyi, and Vinnytsia. Highways are of less importance, although they are necessary for truck transport, which serves agriculture and the food-processing industries. Podilia has 22,800 km of roads, of which 16,300 km are hard surface. Those figures represent 14 percent and 12 percent of Ukraine's road networks respectively. The principal highway from Kyiv and Zhytomyr to Chernivtsi crosses Podilia running through Vinnytsia, Khmelnytskyi, and Kamianets-Podilskyi. Several other major highways cross Podilia from west to east—Kremenets–Koziatyn, Lviv–Ternopil–Khmelnytskyi–Vinnytsia–Uman, Ivano-Frankivsk–Buchach–Chortkiv–Dunaivtsi–Mohyliv-Podilskyi—and from north to south—Lutsk–Kremenets–Ternopil–Chortkiv–Zalishchyky–Chernivtsi and Novohrad-Volynskyi–Shepetivka–Khmelnytskyi.

Three major gas trunk lines cross Podilia from east to west. The Dashava–Kyiv–Moscow line supplies natural gas to Khmelnytskyi, Vinnytsia, and other towns in Podilia. The newer pipelines, such as the Soiuz line (1978), from the southern Urals to Slovakia, and the Urengoi–Slovakia line (1983–4), are used exclusively for exporting gas. (See Pipeline transportation.)

Transport on the Boh River is negligible, and on the Dnister River, limited. Recent completion of the Dnister Hydroelectric Complex has extended navigation on the Dnister.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Marczyński, W. Statystyczne, topograficzne i historyczne opisanie gubernii Podolskiej, 4 vols (Vilnius 1820–2)

Molchanovskii, N. Ocherk izvestii o Podols’koi zemle do 1434 goda (Kyiv 1885)

Batiushkov, P. Podoliia: Istoricheskoe opisanie (Saint Petersburg 1891)

Janusz, B. Zabytki przedhistoryczne Podola galicyjskiego (Lviv 1918)

Białkowski, L. Podole w XVI wieku (Warsaw 1920)

Sitsins’kyi, Ie. Narysy z istoriï Podillia, 1 (Vinnytsia 1927)

Chyzhov, M. Ukraïns’kyi lisostep (Kyiv 1961)

Serczyk, W. Gospodarstwo magnackie w wojewodstwie podolskim w drugiej polowie XVIII wieku (Wrocław 1965)

Shliakhamy zolotoho Podillia, 3 vols (Philadelphia, 1970, 1983) 1960

Ponomariov, A. (ed). Podillia: Istoryko-etnohrafichne doslidzhennia (Kyiv 1994)

Zinchenko, A. Blahovistia natsional’noho dukhu; Ukraïns’ka Tserkva na Podilli v pershii tretyni XX st. (Kyiv 1993)

Volodymyr Kubijovyč, Ihor Stebelsky, Mykhailo Zhdan

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 4 (1993). It was slightly updated in 2020.]

.jpg)