Hromadas

Hromadas. Clandestine societies of Ukrainian intelligentsia that in the second half of the 19th century were the principal agents for the growth of Ukrainian national consciousness within the Russian Empire. They began to appear after the Crimean War, in the late 1850s, as part of the broad reform movement. Being illegal associations they lacked a definite organizational form, a well-defined structure and program, and a clearly delimited membership. Because of police persecution and the mobility of their members, most hromadas existed for only a few years. Even in the longer-lived ones the level of activity fluctuated considerably. Members differed in political conviction; what united them was a love for the Ukrainian language and traditions and the desire to serve the people. The general aims of the hromadas were to instill through self-education a sense of national identity in their members and to improve through popular education the living standard of the peasant masses. Members were encouraged to use Ukrainian and to study Ukrainian history, folklore, and language. They read Taras Shevchenko's works and observed the anniversary of his death. Each hromada maintained a small library of illegal books and journals from abroad for the use of its members. The larger hromadas organized drama groups and choirs, and staged Ukrainian plays and concerts for the public. The hromadas were active in the Sunday-school movement: they financed and staffed schools and prepared textbooks. They also printed educational booklets for the peasants and distributed them in the villages. Avoiding contacts with revolutionary circles, the hromadas regarded their own activities as strictly cultural and educational. It was only at the turn of the century that they began to raise political issues and to become involved in political action. With time a generational difference emerged among the hromadas: societies consisting of young people (secondary-school and university students) became known as young (molodi) hromadas, and those with older members became known as old (stari) hromadas.

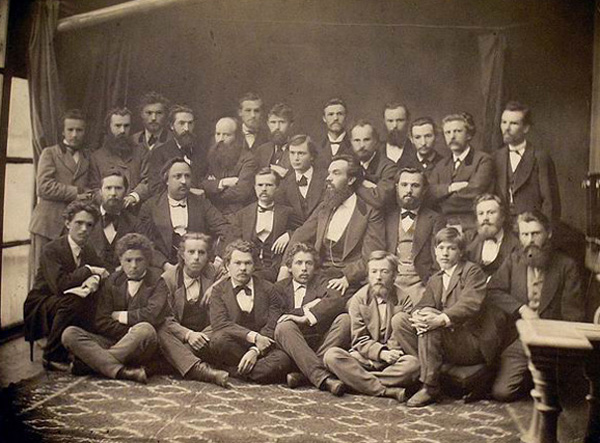

Since most of the information about the hromadas is derived from personal recollections and police records, it is spotty and often contradictory. Some hromadas have left no trace behind. The first hromada, established in Saint Petersburg, was already active by the fall of 1858. It consisted of some former members of the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood, Mykola Kostomarov, Panteleimon Kulish, Taras Shevchenko, and Vasyl Bilozersky, Vsevolod Kokhovsky, Oleksander Kistiakovsky, Danylo Kamenetsky, Mykola I. Storozhenko, Mykhailo Lazarevsky, F. Lazarevsky and Oleksander Lazarevsky, Hryhorii Chestakhivsky, Volodymyr Menchyts, and Yakiv Kukharenko. With financial support from the landowners Vasyl Tarnovsky and Hryhorii Galagan, works of Ukrainian writers began to be published and the journal Osnova (Saint Petersburg) appeared. Saint Petersburg became the center of the Ukrainian national movement at the time. Another hromada outside Ukraine sprang up at the University of Moscow in 1858–9. It maintained close ties with former members of the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood. By the mid-1860s its membership, which included P. Kapnist and M. Rohovych, reached 60. It was uncovered by the police in 1866.

In Ukraine the most important hromada, the Hromada of Kyiv, was organized in 1859 by students who were active in the Sunday-school movement and by members of the khlopomany. It maintained close contact with the Saint Petersburg hromada. In Kharkiv a student circle that collected ethnographic material formed around Oleksander Potebnia at the end of the 1850s, but the first hromada arose probably in 1861–2. In Poltava a hromada arose in 1858. Among its members were Dmytro Pylchykov, Oleksander Konysky, Mykhailo Zhuchenko, Yelysaveta Myloradovych, and Vasyl Kulyk. Another hromada sprang up in Chernihiv probably at the end of 1858. Its most active members were Oleksander Tyshchynsky, Oleksander Markovych, Leonid Hlibov, and Stepan Nis, and its most important contribution to the development of national consciousness was the publication of Chernigovskii listok. The Polish Insurrection of 1863–4 led to a strong anti-Ukrainian campaign in the Russian press and to repressive measures by the government. Petr Valuev's secret circular prohibited the publication of Ukrainian books for the peasants. Ukrainian Sunday schools were closed down, and leading hromada activists such as Pavlo Chubynsky, O. Konysky, and S. Nis were subjected to administrative banishment. These measures disrupted the activities of the hromadas for a number of years.

At the beginning of the 1870s the Hromada of Kyiv, headed by Volodymyr Antonovych, with about 70 members resumed its leading role in the Ukrainian cultural revival. Its activities were disrupted again by the authorities in 1875–6. By this time a strong hromada had emerged in Odesa. Among its founding members were L. Smolensky, M. Klymovych, Mykola V. Kovalevsky, Volodymyr Malovany, and Oleksii Andriievsky. Most of its members shared Mykhailo Drahomanov's ideas, and some of them (Ye. Borysov, Yakiv Shulhyn, Dmitrii Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky) even contributed articles to his journal Hromada (Geneva). The society aided Drahomanov and other Ukrainian activists financially, supported Ukrainian publications in Galicia, financially helped talented individuals to gain an education, and distributed illegal literature. By the time it was crippled with a wave of arrests in 1879, the hromada in Odesa had over 100 members. Besides the Hromada of Kyiv this was the only hromada that lasted for several generations.

In the 1880s those members of the Odesa hromada who had avoided exile turned to purely cultural activities. They supported the development of Ukrainian theater in southern Ukraine, published collections of the best current works by Ukrainian writers, helped Mykhailo Komarov compile Russko-ukrainskii slovar' (The Russian-Ukrainian Dictionary, 4 vols, 1893–8), and made an unsuccessful attempt to publish a journal. Thanks to a more tolerant governor in the Kherson gubernia, the Odesa hromada was more active at the time than the Hromada of Kyiv. In the 1890s a student hromada emerged in Odesa but it did not survive long. The old hromada, under pressure from younger members, gradually became involved in some political activity. In Kyiv several student hromadas sprang up in the 1880s: a study circle inspired by Mykhailo Drahomanov's ideas was organized by O. Dobrohraieva at the Higher Courses for Women; a political group guided by Mykola V. Kovalevsky advocated a constitutional federation and spread propaganda among students; and several smaller circles were formed at particular schools. In the 1890s L. Skochkovsky organized a hromada of theology students, which consisted of about 30 members including Oleksander Lototsky and Polikarp Sikorsky. In 1895 a student hromada, which included H. Lazarevsky, Dmytro Antonovych, Vasyl Domanytsky, and Petro Kholodny, arose at Kyiv University. A number of other higher schools in Kyiv had their own secret hromadas. There was little contact between the old hromada, which shied away from political involvement, and the young hromadas. In the autumn of 1901, the Women's Hromada in Kyiv was founded. This clandestine women's group organized by prominent members of Kyiv's nationally conscious Ukrainian intelligentsia existed until the Revolution of 1905.

In Kharkiv there was a loosely organized, informal old hromada consisting of such scholars and writers as Oleksander Potebnia, Dmytro Pylchykov, Volodymyr Aleksandrov, Petro S. Yefymenko, and his wife Aleksandra Yefymenko. A student hromada headed by Ovksentii Korchak-Chepurkivsky and including members such as Mykola V. Levytsky and Yevhen Chykalenko took shape in 1882. Two years later a political hromada that embraced the principles of the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood and of Mykhailo Drahomanov was organized by Volodymyr Malovany, M. Levytsky, I. Telychenko, and N. Sokolov. Another politically oriented student hromada was founded in 1897 by Dmytro Antonovych, Yurii Kollard, Mykhailo Rusov, Borys Martos, Oleksander Kovalenko, Bonifatii Kaminsky, Lev Matsiievych, and others. By 1899 it had over 100 members, and in 1904 it merged with the illegal Revolutionary Ukrainian party (RUP), which previously had been founded by the hromada. In Chernihiv a hromada with members such as Illia Shrah, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, I. Konoval, and Borys Hrinchenko was active at the end of the 1890s, and in Poltava a hromada was headed by M. Dmytriiev.

Outside of Ukraine a large and active student hromada existed in the 1880s in Saint Petersburg, whose higher schools attracted many students from Ukraine. Hromada members smuggled illegal literature into Russia, studied Mykhailo Drahomanov's works, organized a choir, and celebrated Taras Shevchenko's anniversary each year. In 1886 some of its members composed a political program and formed the Ukrainian Socialist Revolutionaries. Towards the end of the 1890s an old hromada was formed in Saint Petersburg by Yevhen Chykalenko, Volodymyr M. Leontovych, O. Borodai, Petro Stebnytsky, and others.

At the beginning of the 20th century as students became more nationally conscious and politically engaged, hromadas proliferated in gymnasiums, higher schools, and universities. The Revolution of 1905 drew attention to political issues and loosened restrictions on political activity. The student hromada in Kyiv had evolved into a branch of the Revolutionary Ukrainian party by 1904 and in 1905 was decimated by arrests. It reorganized itself in the following year and fell under the influence of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Workers' party. In 1906 new hromadas arose at Kyiv University, the Higher Courses for Women, and the Kyiv Polytechnical Institute. In order to gain official recognition these societies avoided political action. The student hromada of Kharkiv (est 1907), with a membership of about 150, was a legal, chartered society. In Odesa there was a short-lived (1903–6), illegal student hromada. Outside of Ukraine the Saint Petersburg student hromada in 1903 united over 300 Ukrainian students belonging to various school hromadas into one organization. Almost all members (about 60) of this hromada, which was headed by V. Pavlenko, H. Bokii, and then Dmytro Doroshenko, were members of RUP. A small student hromada in Dorpat (Tartu) (est 1898) was headed by Fedir Matushevsky. In Moscow the Ukrainian student hromada (est 1898) staged concerts and plays and avoided political activities. A small student hromada was organized in Warsaw by V. Lashchenko in 1901.

At the end of the 19th century efforts were made to co-ordinate the activities of the widely dispersed old and young hromadas. At the initiative of Volodymyr Antonovych and Oleksander Konysky, a conference of members of various hromadas was held in Kyiv in 1897, and the General Ukrainian Non-Party Democratic Organization was established. In August 1898 the first Ukrainian student conference was held in Kyiv and was attended by representatives of young hromadas. A year later the second conference was held. The purpose of the third conference, held in Poltava in June 1901, was to draw the student hromadas into revolutionary activity under the leadership of the Revolutionary Ukrainian party. A fourth student conference was called in Saint Petersburg in 1904.

As reaction set in and restrictions on political activity were tightened, hromada members continued to be active in various cultural societies, Prosvita societies, and other organizations until the Revolution of 1917. The traditional name hromada was later used by Ukrainian émigrés, particularly students, for their organizations.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chykalenko, Ie. Spohady (1861–1907) (Lviv 1925–6; 2nd edn, New York 1955)

Vozniak, M. ‘Z zhyttia chernihivs'koï hromady v 1861–63 rr.,’ Ukraïna, 1927, no. 6

Iehunova-Shcherbyna, S. ‘Odes'ka hromada kintsia 1870-kh rokiv,’ Za sto lit, 2 (1928)

Riabinin-Skliarevs'kyi, O. ‘Z zhyttia odes'koï hromady 1880-kh rokiv,’ Za sto lit, 4 (1929)

Hnip, M. Hromads'kyi rukh 1860 rr. na Ukraïni (Kharkiv 1930)

Lotots'kyi, O. Storinky mynuloho, 3 vols (Warsaw 1932–4)

Z mynuloho. Zbirnyk 2 (Warsaw 1939)

Antonovych, M. ‘Koly postaly hromady?’ Naukovyi zbirnyk UVAN, 3 (1977)

Stovba, O. ‘Ukraïns'ka students'ka hromada v Moskvi 1860-kh rokiv,’ Naukovyi zbirnyk UVAN, 3 (1977)

Boldyriev, O. Odes'ka hromada: Istorychnyi narys pro ukraïns'ke natsional'ne vidrodzhennia v Odesi u 70-i rr. XIX–pochat. XX st. (Odesa 1994)

Mykola Hlobenko, Taras Zakydalsky, Arkadii Zhukovsky

[This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 2 (1989).]